©REESE PALLEY from CRUSING WORLD September 1995

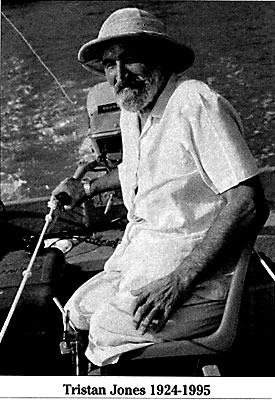

He was a furious man. a man against the gods. Tristan Jones died as he lived, far away from home in some part of the iconoclastic dream thai was his life. He never had a serene moment. Whatever good came to him arrived with a price, and the good, according to Tristan, was not worth the money he traded for it.

The money on which he survived came from the books of sailorly dreams for which he was famous. It has been argued that all of the adventures did not happen and, if they did. that Tristan added to and embellished what were essentially small events. It is a dismal argu- ment against a man whom no one could ever aptly describe with the term small. It was no small feat to wrench a meager living out ol his quill. Fiercely independent, it was no small feat to overleap illness, to pass off the loss of one leg by bestowing the facetious name Outward Leg on his new vessel, it was even less of a small feat to lose his other leg, and keep sailing.

Those of us who sail and dream, and who find that our dreams are just an approximation of reality, reveled in Tristans adventure. In his books he let us join him in now impossible adventures that we would wish for ourselves. That he sailed in the most difficult climes is fact. His confrontations and battles with pettty officials were fact. How he bested them, how he turned impossible odds to great victories are neither fact nor fiction. Tristan's battles against the odds, as he described over and over in his books, were little more than his irascible railing against the larger officialdom of fate.

I have two true tales to tell of Tristan that give thr flavor of the man. There came a time when I innocently sought to convert an ancient little harbor built by Constantine on the Black Sea into a modem Romanian marina. The project was beset by pettiness and obstacles. In trying to deal with this I came to believe that only a Tristan Jones could smash through the barriers daily set upon us. I asked him to come to Romania and be the commodore of the Constanza Yacht Ciub and the captain of the port. His job, which he accepted with a joyous glint in his eye, was to get these recalcitrant folk into shape.

He stormed into Romania on his one good leg and set about, as only he could, making a silk purse out of a sow's ear. He spent the worst winter of his life in that small harbor, roaring up and down the docks in his wheelchair, spreading panic and terror. In the spring he confessed to me that, despite towering rages and brutal tantrums, the battle was lost. Because I had seen him through worse times, I was curious to know how he had failed to conquer mere bureaucrats when he had so often and so handily conquered the gods themselves.

"I'll tell you, boyo, the gods were easy. They stood and fought. With the Romanians it was like jousting with shadows. The worst enemy I never bested."

But years later his memory was still burned with the branding iron of fear into the sailors of Constanza. When I would go down to the harbor to look after my vessel, awkwardly stilted on the hard, their mouths would whisper half in terror, half in awe, "Where is Captain Jones?"

But their eyes really would be saying, "God grant that he never returns." The second tale of Tristan is a lesson in turning adversity into advantage. Tristan had the will and, being a Welshman, he had the wit to turn back ill slings of fate as if with the shield of Odysseus.

The place was the most flawed Rhodes harbor that one could imagine: tiny, laced with ancient lost chains crisscrossing its bottom acting as a magnet for every sailboat in the Med. Tristan was there in the curious trimaran, Outward Leg, that he had built after losing his first leg.

The boat was built to allow him to haul himself about and provided numerous places where a one-legged man could wedge himself into a standing position. Tristan, who was known to take a drink now and then, opined that his boat would be a perfect pub:

"No matter how drunk or how few legs, it won't let me fall down."

He was leaving for a passage eastward and, because almost everyone in the harbor knew Tristan, a cabal was formed to coordinate their boats' whistles, horns and sirens at the moment Outward Leg passed through the fabled gates of Hercules. The moment came. All the English-speaking boats started together and, sensing something was up, the rest of the boats in the harbor joined in. The whooping was impressive. As he slipped through the narrow entrance, a forgotten trailing line stopped Outward Leg dead in the entrance and pitched Tristan, who was at the moment waving in appreciation to the, honor accorded him, flat on his back.

The harbor went dead quiet. It was hard to say who, the honorers or the honoree, was more embarrassed. Tristan s mate, a young Thai lad, slipped over the side and emerged with the line in one hand and a mucky, dripping bundle of something in the other. Tristan, ever mindful of image, hollered over to those of us standing shamefacedly at the entrance.

"Never mind, mateys, the Sea Gods laughed today They tangled my line onto the lost Treasure of the Argonauts. I'll write about the Treasure in my next book."

What we now all have come to recognize, perhaps a nanosecond too late, is that the true Treasure of the Argonauts was Tristan Jones himself.

|

The voice of a sailing legend may now be quiet, but It has been immortalized in the literature of the sea: |

Off the headland of Laem Kanoi, a sea eagle, pale golden, gleamed in the low late-afternoon sun. He flew over to inspect us from way above, and as Gabriel charged forward at full pelt, he decided to join in the fun. He dived down ahead of us a dozen times or more and zoomed up again to the heights of a marvelous sky. Once or twice he aimed himself straight down to within inches of our masthead, then soared up a hundred yards and more straight up into the God-givenen heights. For me and my crew, these ...sailing trials were passages of learning and discovery. I found that I and all three of our men were bred-in-the-bones sailors. All that I needed to explain to them were the mechanics of things. The forces of the wind and sea, for them. needed no explanation. It's as though we all had race-memory from our seafaring ancestors. For me, as the sea eagle dived and soared, it was joy and deliverance. That sea eagle and I shared a celestial joke: "What is life about?" He seemed to he crying. "This!"

Excerpted from Adventures Of A Wayward Sailor by Tristan Jones (Sheridan House, Dobbs Ferry, NY)